Valuation advice from Corilon violins. On the inital valuation, age, provenance, value and certificate of an old violin.

A violin is in the eyes of the owner a trusted musical partner, and at the same time it is full of enigmas which are never fully understood. Over the course of time, most musicians develop a deep and intuitive kind of interaction with their instrument, yet as soon as a decision has to be made about buying the best violin or the about the violin value, there are endless questions. For many years our violin experts have helped musicians around the world as they look for the valuation of their old violin or stringed instrument. This article is intended to provide some information on the initial violin valuation which is especially important as you make your choice. Gain valuable insights into the cost of violins in our comprehensive overview of old and new violin prices.

Favored instruments: Cremona violins | Italian violins | Fine violins | Antique violins

Overview of our guide to selecting and purchasing a violin:

- The general signs of a quality violin

- The age and provenance of a violin

- The old violin value, appraisals, certificates and valuations

General signs of quality in a violin

How do you recognise a good violin? What is a violin worth? How is the old violin value determined and which is the best violin?  When you want to determine the quality and value of a stringed instrument, one reliable point of departure is to look at the materials used to craft it. The first thing to focus on is usually the grain of the wood not only on the body of the violin, but its neck and scroll as well. Fine to moderate grain is generally seen as a sign of quality when it comes to spruce, which is commonly used for the top. The even lines of the grain also indicate well-selected tone woods. Maple, which is used for the back, ribs and neck of most stringed instruments, often features interesting flaming, and this too provides visible evidence about the structure of the tonewood.

When you want to determine the quality and value of a stringed instrument, one reliable point of departure is to look at the materials used to craft it. The first thing to focus on is usually the grain of the wood not only on the body of the violin, but its neck and scroll as well. Fine to moderate grain is generally seen as a sign of quality when it comes to spruce, which is commonly used for the top. The even lines of the grain also indicate well-selected tone woods. Maple, which is used for the back, ribs and neck of most stringed instruments, often features interesting flaming, and this too provides visible evidence about the structure of the tonewood.

An old violin with a spruce top that has evenly-distributed fine to moderate grain and a back of beautifully flamed maple already provides initial clues that it may be a high-quality instrument. But as always, there are exceptions to every rule, and that is as much the case in the world of violin-making as it is in other demanding forms of artisanry. For example, bearclaw spruce is a type of timber highly prized in violin making due to its good physical properties, yet this wood is also known for the irregular streaks (the "bearclaws") in its grain. Furthermore, there are certain regional traditions and individual luthiers who outright prefer to work with unconventional kinds of wood. It appears as if many Italian masters wanted to demonstrate their experience and expertise by deliberately selecting cuts of wood with irregular grain or even worm tracks. More often than not, these aesthetically unusual but outstanding-sounding violins confirmed that they chose well. Fine violins have been crafted from such "inferior" material since Guarneri's day.

When it comes to the wood used to make a violin, the fingerboard is in a category of its own. Premium violins built before approximately 1900 were usually fitted with a fingerboard of solid ebony, whilst other hardwoods such as beech were seen as less-valuable alternatives. Occasionally softer woods were used, but this did not have an impact on the sound. Older violins in particular, e.g. Baroque-era instruments, often had fingerboards made of soft wood that was then given an ebony veneer or perhaps even simply varnished in black. Areas where there has been a great deal of wear gradually reveal the lighter-coloured material underneath. At the beginning, ebony was a truly rare and expensive wood, and its very use can be understood as an acknowledgement of the fact that violins were made for a refined clientele, and the quality had to reflect this. This statement no longer applies to newer instruments, however: today there is enough ebony available (albeit usually in poorer quality) to produce even simplest industrially-manufactured violins.

Not only is the wood a reflection of how good an old violin is, the varnish also reveals quite a bit about differences in quality. It is well known that the old Italian masters of Cremona used varnishes that have become the stuff of legend, and even though nowadays varnish is no longer considered critical to a violin's sound, it nevertheless remains an eye-catching calling card for the luthier's art. Contemporary violin makers such as Christoph Götting spent a great deal of time observing and successfully imitating the methods of the old masters. An old violin's varnish plays a large part in determining its origins (see below), and at the same time it indicates the care and time that went into its construction. Many Italian violins are famous for their rich oil varnish, and some luthiers applied over 40 coats before they deemed the instrument ready to play. Since oil varnish also dries very slowly, it was not uncommon for several months to pass before a violin's varnish was complete. Spirit-based varnish can be handled much more quickly, and it sometimes forms delicate crackling but may nevertheless be of very high quality. In some situations spirit varnishes dry as they are being applied, which means they demand a great deal of artisanal confidence and experience – unlike oil varnishes, some of which never fully harden and can thus always be slightly touched up. Spirit varnishes are not a fundamental sign of a less valuable instrument, however; on the contrary, they may be evidence of a craftsman's well-trained and practiced hand. By contrast, nitrocellulose lacquer or synthetic resin, which are extremely common on Chinese mass-produced instruments, are a clear sign of low quality. These varnishes can have a negative effect on the violin's ability to vibrate, especially if they were applied with certain industrial spraying techniques. What's more, they are unpleasant both optically and in terms of the unpleasant odour they give off for at least the first several weeks and months after they were made.

Not only is the wood a reflection of how good an old violin is, the varnish also reveals quite a bit about differences in quality. It is well known that the old Italian masters of Cremona used varnishes that have become the stuff of legend, and even though nowadays varnish is no longer considered critical to a violin's sound, it nevertheless remains an eye-catching calling card for the luthier's art. Contemporary violin makers such as Christoph Götting spent a great deal of time observing and successfully imitating the methods of the old masters. An old violin's varnish plays a large part in determining its origins (see below), and at the same time it indicates the care and time that went into its construction. Many Italian violins are famous for their rich oil varnish, and some luthiers applied over 40 coats before they deemed the instrument ready to play. Since oil varnish also dries very slowly, it was not uncommon for several months to pass before a violin's varnish was complete. Spirit-based varnish can be handled much more quickly, and it sometimes forms delicate crackling but may nevertheless be of very high quality. In some situations spirit varnishes dry as they are being applied, which means they demand a great deal of artisanal confidence and experience – unlike oil varnishes, some of which never fully harden and can thus always be slightly touched up. Spirit varnishes are not a fundamental sign of a less valuable instrument, however; on the contrary, they may be evidence of a craftsman's well-trained and practiced hand. By contrast, nitrocellulose lacquer or synthetic resin, which are extremely common on Chinese mass-produced instruments, are a clear sign of low quality. These varnishes can have a negative effect on the violin's ability to vibrate, especially if they were applied with certain industrial spraying techniques. What's more, they are unpleasant both optically and in terms of the unpleasant odour they give off for at least the first several weeks and months after they were made.

Older violins often undergo gradual changes in the appearance of their varnish, and this too says something about their quality. One factor here is the patina, which many aficionados of historic violins appreciate. It is evidence of a natural ageing process which may occur to varying degrees, depending on the ingredients in and nature of the varnish. Crackling is another process which can be interpreted in different ways: it may indicate that the varnish was poorly formulated, yet it can just as easily be seen as an aesthetically pleasing kind of art which was created by coincidence. Even scratches can only be attributed to their respective mechanical cause sometimes; after long and intense use, a violin with a soft oil varnish will naturally show more wear and tear than one with a harder spirit varnishes. These traces often communicate a great deal; for example, there may be many minor flaws around the fingerboard if a previous owner played a great deal in high positions. An old violin with such marks invariably spent a long time in the hands of good musicians who had the ability to play the upper registers. And the more they were satisfied with their instrument, the more traces of use they will have left. Varnishes and the wood they coat can also undergo significant changes in colour over the years. Taken as a whole, these factors all contribute to the typical aesthetic of an old violin — the varnish may no be longer flawlessly smooth and may have an uneven colour, but its overall character is distinctive and charming. For generations, several violin makers have deliberately attempted to imitate this look by "antiquing" their new violins. As a result, the art of antiquing varnish has become a violin-making discipline unto itself since the 19th century. It should not be overlooked, because it can also indicate a well-crafted instrument.

Older violins often undergo gradual changes in the appearance of their varnish, and this too says something about their quality. One factor here is the patina, which many aficionados of historic violins appreciate. It is evidence of a natural ageing process which may occur to varying degrees, depending on the ingredients in and nature of the varnish. Crackling is another process which can be interpreted in different ways: it may indicate that the varnish was poorly formulated, yet it can just as easily be seen as an aesthetically pleasing kind of art which was created by coincidence. Even scratches can only be attributed to their respective mechanical cause sometimes; after long and intense use, a violin with a soft oil varnish will naturally show more wear and tear than one with a harder spirit varnishes. These traces often communicate a great deal; for example, there may be many minor flaws around the fingerboard if a previous owner played a great deal in high positions. An old violin with such marks invariably spent a long time in the hands of good musicians who had the ability to play the upper registers. And the more they were satisfied with their instrument, the more traces of use they will have left. Varnishes and the wood they coat can also undergo significant changes in colour over the years. Taken as a whole, these factors all contribute to the typical aesthetic of an old violin — the varnish may no be longer flawlessly smooth and may have an uneven colour, but its overall character is distinctive and charming. For generations, several violin makers have deliberately attempted to imitate this look by "antiquing" their new violins. As a result, the art of antiquing varnish has become a violin-making discipline unto itself since the 19th century. It should not be overlooked, because it can also indicate a well-crafted instrument.

In other words, the varnish provides some important information about the craftsman standards with which it was made, but beyond that, there are another few details which also help you assess an instrument's quality. Special tools and extensive experience are both needed to review important acoustic characteristics such as how the thickness of the top and back were crafted. However, even lay people can often see for themselves whether the scroll and the purfling were made carefully and by hand. On an old violin, these parts serve as a good point of orientation, even though they do not provide any information about the violin's musical properties. Once again, however, the Italian violin-making tradition offers numerous exceptions to the rule, dating all the way back to famous masters such as Guarneri del Gesù. Some such instruments show very sloppily crafted details but still possess an exceptional sound. Another exception to the rule is the manufactured work from the French violin-making town of Mirecourt, which was created with the objective of providing instruments that were as good and as affordable as possible. Particularly in the 19th century and the fin de siècle period, these violins sometimes only had traced-on purfling, which significantly decreased the time needed to produce them. Nevertheless, amongst these violins there are several instruments with a truly good sound and outstanding playing characteristics which are certainly adequate for the standards of an advanced student musician. And of course, there are luthiers who emphasise the overall "cosmetics" of an instrument at the expense of its musical quality. The result is that sometimes there are exquisite-looking violins with features such as a meticulously carved scroll, complicated purfling and perfectly executed antiqued varnish, but their sound is mediocre. In assessing violins, an important rule of thumb is never to focus on a single characteristic by itself, but rather to look at the instrument in its entirety.

Last but not least, older violins, violas and especially the large cellos commonly have undergone repairs, which themselves do affect the value of a stringed instrument and can be a sign of quality work. For example, bushed and reworked peg holes usually indicate that the instrument was in use for a long time and was frequently tuned, which in turn meant that the peg holes expanded due to the friction from the pegs and thus had to be readjusted. Furthermore, a new neck or new scroll is no longer considered to be damage that lowers the value of an instrument; instead, this confirms that the violin was good enough to justify such extensive maintenance work. This is also true of cracks in the top, back or ribs, as long as the repairs were done properly and do not have an effect on the sound. The quality of these repairs can often be a good signal about the instrument's value, and highly respected restorers often sign their work by applying their own label in the violin's body.

For those who see their violin as a musical instrument (as opposed to a decorative object), once the material and craftsmanship have been assessed, the next step is to examine the sound and playing characteristics. It goes without saying that individual preferences and personal prerequisites are the most important factor here: everything from the volume of the instrument's voice to its timbre all the way to its response depends on who is playing the violin and what musical goals they have.

The Corilon online violin shop places great importance on presenting an accurate description of each instrument's acoustic character, and we further document its sound with an audio clip to provide an initial point of orientation. By offering an extended return policy, we also provide additional security as you explore the musical personality of your instrument.

The age and provenance of a violin

The advantages of old violins vis-à-vis new violins – and vice versa – is one of the most widely-discussed issues in the world of stringed instruments. Nearly every six months a new article makes its way through the media in which a scientific study claims to have found definitive proof for one standpoint or another. For the most part, these alleged revelations only point towards a one-dimensional approach which can never adequately address a phenomenon as complicated as a stringed instrument. The quality of an old violin — especially of the finest historic master instruments — can never be traced back to a single factor, such as a secret kind of varnish, a specially textured wood, climatic conditions where the violin was crafted, or the effects of certain fungi. None of these alone can turn a violin into a masterpiece. What's more, the ever-popular blind comparisons in which the acoustics of old and new violins are directly contrasted with each other make one thing clear above all: they reveal a dubious understanding of the way musicians deal with their instruments. They have to interact with their violins intensely so they can fully understand and make the most of its tonal opportunities.

In other words, there is no rule stating that old violins always sound better than new ones. There can, however, be no doubt that countless historic violins have an unmistakable and distinctive maturity in their sound. And this in turn may be due to anything ranging from the grain of the wood, the individual way the wood aged, or advantages of a particular design, not to mention the art and agile hand of its maker. At Corilon violins, our enthusiasm for the personalities of these older instruments is what informs our work and our catalogue, yet we also appreciate contemporary violins of outstanding quality.

The provenance, in other words the fact that an old violin comes from a particular region or luthier is neither inherently a guarantee of quality nor a shortcoming. The many varying traditions have all resulted in certain distinctive identifying traits. When you select a violin, these regional differences are not primarily a question of quality, since bad instruments were (and are) produced everywhere, and there is no place on earth which produced only good violins. Instead, you should focus on the acoustic profile and its ability to create the sound you desire. As a rule, for example, Italian violins are highly praised for their soft, melting undertone which is often accompanied by an unconventional and ingenious aesthetic design. Good French violins are characterised by a dominant sound that is ideal for soloist performance, and many experienced musicians prefer these instruments because of their extreme precision. Others may incline towards the comparatively strict sound of English violins for nuanced ensemble playing.

Many different regions favoured particular nuances in craftsmanship which are often evident only to the trained and experienced eye, although there are also many far more conspicuous features that frequently serve as proud indications of a local tradition. One prominent example here is the very striking and eye-catching design favoured by the Hopf violin-making dynasty in the Saxonian village of Klingenthal: it is easily identified by its slightly "angular" upper bout. Many of these violins, including those with more conventional contours, also feature the traditional Vogtland brown varnish against a striking yellow background that shines through. As a general rule, an old violin's varnish and colourful ornamentation provide good information about its provenance, such as the extremely dark, if not almost black, varnish found on many 19th-century Bohemian and Austrian instruments. On a similar note, French violin making commonly involves a very elegant aesthetic and blackened edges on the body and especially the scroll. Regional characteristics of this kind should not be confused with prominent individual characteristics which were inspired by the personal style of certain master luthiers. The famous Italian luthier Maggini developed flourishes such as double purfling or a scroll with an additional winding, and they were soon imitated around the globe.

The value of a violin, appraisals, certificates and valuations

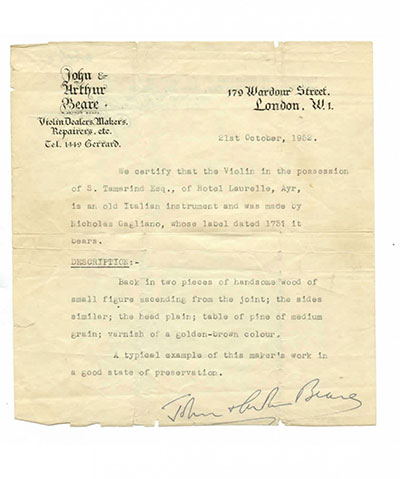

Today, violins are sold at a greater spectrum of prices than ever before, ranging from extremely cheap mass-produced instruments (usually from China) all the way to priceless historic collectors' items. This divergence in value started in the late 18th century: publishing companies and factories first made it possible to churn out large numbers of simple and affordable violins, and simultaneously the exceptional traits of historic instruments made by Stradivari, Guarneri and other classic masters were being discovered. The exceptional quality of the latter meant that musicians became more interested, although soon collectors and investors followed, and general demand led to a sharp increase in prices. In the second half of the 20th century, these masterpieces by famous luthiers ultimately became objects of speculation, and in some cases prices rose 200 times over. The development of value and price of fine stringed instruments also opens the door to fraud and forgery that exploits the ignorance and naivety of most musicians. The purchase of an expensive violin that exceeds a certain price range should be considered only from legitimate sources, via the retailer; from private individuals if offered with a appraisal or certificate of a recognized expert.

Whilst cheap violins have never been as affordable and expensive instruments never as pricy as they are today, these two extremes are viable options for only a very few musicians. For years now, even outstanding soloists have not been able to afford valuable historic instruments, which is why old violins are often made available to them as part of a scholarship or a donation from a patron of the arts. On the other end of the scale, today's factory-made violins include many items which are sold at bafflingly low prices. This is a response to the demand amongst the many beginners and students, but most of the instruments are not suitable for learning how to play. It is certainly true that most people's budget for buying a violin is quite modest, and having the wide range of acoustic possibilities which a top-quality master instrument provides is a luxury which is not critical in the first few years. That said, however, a proper musical education will not be a success unless you have an instrument with a good sound which is responsive, "forgiving" and motivates you. Trying to meet this standard obviously means production cost can be rationalised only to a limited extent, which in turn creates a natural limit on price structures. It is thus truly astonishing that there is hardly any public discussion about whether environmental and social principles are being upheld in the mass production of stringed instruments. The very fact that new sets of violins and bows are available for less than €100 should give rise to numerous critical questions.

Old violins provide opportunities to offset these countervailing tendencies. Today, fine stringed instruments with certificate or appraisal and major names on the labels have become collectors' items, regardless of the violins' musical value, whilst violins with a heritage that is not fully known or is less in demand often have brilliant playing and acoustic characteristics – and are available at surprisingly low prices. Such instruments sold by reliable sources feature extensive documentation that takes full advantage of all of the technical tools the Internet has to offer. Furthermore, the violin's value is determined by experts after the instrument was professionally set up, thus ruling out any hidden repair costs. This high standard is the guideline for the Corilon violins online catalogue, which also features our client-friendly terms and conditions, including an extended 30-day return policy. By providing extensive consultation, we help our clients select the right violin for their needs — the perfect instrument with the format and musical character to suit each musician's individual style.

Old violins provide opportunities to offset these countervailing tendencies. Today, fine stringed instruments with certificate or appraisal and major names on the labels have become collectors' items, regardless of the violins' musical value, whilst violins with a heritage that is not fully known or is less in demand often have brilliant playing and acoustic characteristics – and are available at surprisingly low prices. Such instruments sold by reliable sources feature extensive documentation that takes full advantage of all of the technical tools the Internet has to offer. Furthermore, the violin's value is determined by experts after the instrument was professionally set up, thus ruling out any hidden repair costs. This high standard is the guideline for the Corilon violins online catalogue, which also features our client-friendly terms and conditions, including an extended 30-day return policy. By providing extensive consultation, we help our clients select the right violin for their needs — the perfect instrument with the format and musical character to suit each musician's individual style.

Related articles:

Corilon violins certificates and appraisals

The violin wolf tone: Taming the wolf in a stringed instrument

Ernst Heinrich Roth: a rediscovered master

Hopf: a dynasty of Vogtland violin makers

Jérôme Thibouville-Lamy - J.T.L.

Bow maker and entrepreneur H. R. Pfretzschner

Contemporary violin makers - the modern artisans

Mittenwald violin makers - contemporary masters

Violin makers from China and Taiwan

E. Sartory: the modern classic of bow making

Guide to silent electric violins

Related information:

New arrivals in our catalogue