Although violin labels contribute absolutely nothing to the sound of an instrument, they have always attracted a great deal of attention. How can real labels be distinguished from fake ones, what markings and hidden messages are there besides them - and why do some violins have several labels from different makers?

Overview

- Violin labels - form and use

- Brand marks and signatures as alternatives and supplements to the violin label

- History of the violin label

- Determining the authenticity of a violin label

- Repair label

- Sources for research on violin labels

Violin labels - form and use

Violin labels are manufacturer's information in the form of small paper labels stuck inside the body of a stringed instrument with a bit of glue. The German word "Geigenzettel" does not exclusively refer to labels in violins, but also functions as a generic term - analogous to "Geigenbauer" - for labels in violins, violas, cellos and other stringed instruments. Similar markings occur in other instruments as well, and are especially common in stringed instruments of the European musical tradition throughout the ages.

Traditionally, a violin label contains:

Traditionally, a violin label contains:

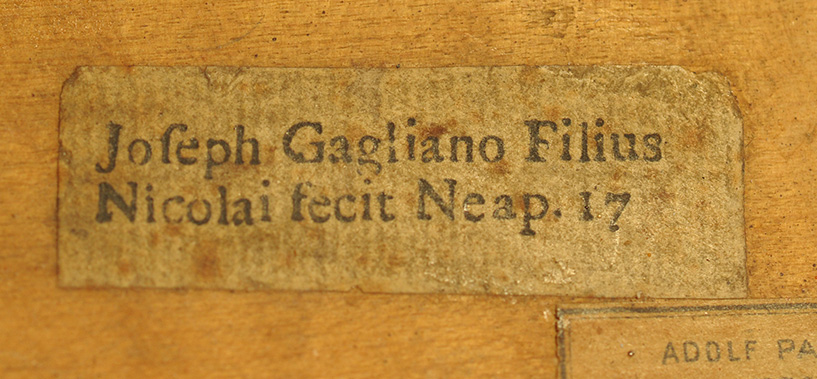

- the name of the violin maker

- an indication of the place,

- the year in which the instrument was made,

- if applicable, a work number (opus),

- graphic marks (logos), not infrequently with a religious reference,

- a formula such as "fecit" or "me fecit" - "has built" or "has built me" respectively,

- graphic decorative elements in the style of the respective epoch.

However, most violin labels give only the name, place and year. The usual place for a violin label to be affixed is on the bottom below the F-hole on the bass bar side; the size usually varies with lengths up to about 10 cm and heights up to about 5 cm. The labels are cut from paper of different grades and usually printed. Fully handwritten violin labels are comparatively rare, but occur in all periods of violin making history. Individual handwritten indications such as a signature, year and work number, on the other hand, are quite common with printed slips and usually also serve the purpose of personal authorization by the violin maker. The year is often pre-printed to the thousands, or more rarely to the hundreds, and then added by hand.

Brand marks and signatures as alternatives and additions to the violin label

As an alternative or in addition to the violin label, stringed instruments are marked with a brand (also: brand mark) and other handwritten signatures. A traditional place to place a branding stamp is on the outside of the back, on the button or directly below it. However, brand marks can also be found inside the body; some masters even stamp the top and back individually to document the authenticity of all parts of the instrument. Hidden marks in some cases probably also reflect concern that the instrument might be anonymized by removal of the original label or claimed by competitors as their own work. Additional handwritten signatures usually serve the same purposes as branding marks, but sometimes include dedications or references to biographical or historical data, such as in this violin by Louis Moitessier.

History of the violin label

Like the question of the origins of the violin, the early history of the violin label will probably ultimately remain hidden from research, since original instruments in the European context have only been preserved since the Renaissance, and labels can already be found in them. At the same time, their information always requires historical classification and interpretation, even if they are used in the comparatively straightforward environment of artisanal workshops, often run by families, which formed the authoritative frame of reference especially for the earlier history of violin making until the late 18th century. Thus, it is true for all information on violin labels that it does not necessarily have to correspond to the full truth: Especially in well-established, successful workshops, it was good practice over the centuries to continue using the slips of the father or predecessor after the business had been inherited or transferred.

In addition, with the introduction of the division of labor in "publishing" and industrial production, the violin label developed more and more into a "model label" that gave - more or less justified - references to classical models of the violins produced in large numbers, but often enough was simply intended to use the sound of big names for advertising, if not to deceive unsuspecting customers. This practice is responsible for the "Stradivari flood", the enormous amount of 19th century Saxon or Mittenwald violins with often quite well made replicas of historical Stradivari slips. While earlier eras of violin making always knew unmarked instruments, today the violin label is standard on instruments of all quality classes.

This contrasts with another practice that was cultivated, for example, by the famous house of Lendro Bisiach in Milan: The "adoption" of selected instruments that were finished to varying degrees in their own workshop and then sold under their own label. Many outstanding Bisiach instruments, which today are traded at good prices and are popularly played, are of Saxon origin - and received not only the varnish but also the famous master's blessing in the form of his note.

Determining the authenticity of a violin label

The above-mentioned need for interpretation of the violin label naturally also raises the question of how imitations and forgeries can be reliably distinguished from original labels. Research on musical instruments uses comparisons of the paper used, the printing technique, the contents and, of course, not least, the instruments in which the slips are found. Apart from clumsy forgeries or facsimiles that are deliberately kept recognizable, it is usually impossible for laymen to tell whether a slip is authentic or not.

Repair labels

Fine stringed instruments in particular are often doubly marked and bear, in addition to the maker's label, other labels, stamps or signatures that indicate repairs or alterations - a practice that the great master luthier and teacher Otto Möckel strongly condemned in his standard work "Geigenbaukunst": "Furthermore, one should not defile violins with repair labels. However, if one does not want to suppress one's vanity, one should make these labels as small as possible." This harsh verdict, however, should be countered by historical honesty and respect for the collegial performance for which repair notes also stand and which have their unconditional right, especially in the case of major interventions in historical instruments.

Sources for research on violin labels

The standard works on the history of violin making by Luetgendorff, Vannes, Jalovec and others contain extensive collections of violin slip reproductions. In addition, the Leipzig publisher and musical instrument collector Paul de Wit published "Geigenzettel alter Meister," a comprehensive work presenting slips up to the mid-19th century, the first edition of which can be downloaded here or read online.