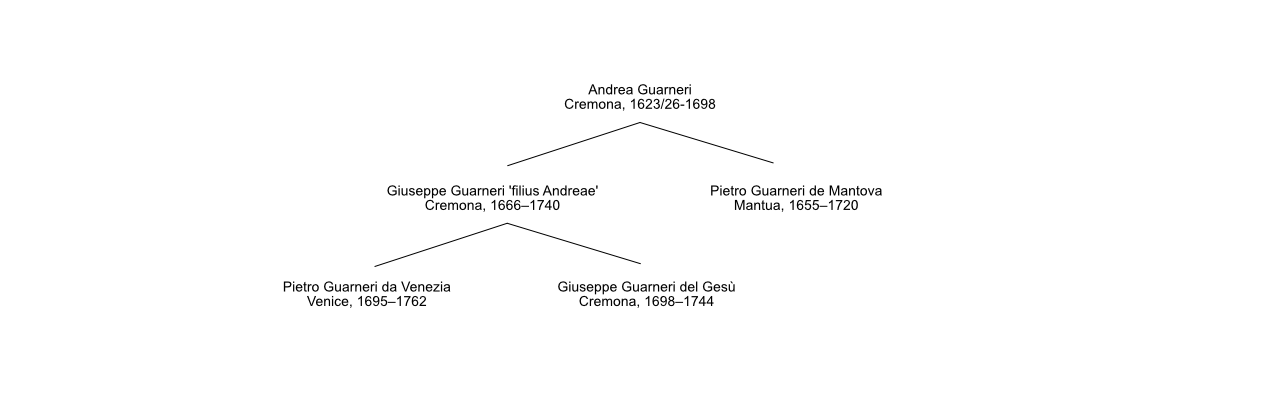

Andrea Guarneri – the pater familias

The life and work of Andrea Guarneri, a major historic figure and the pater familias of a great family of Cremonese luthiers Guarneri, are both closely linked to the history of the Amati workshop. A boy from the farming village of Casalbuttano, he learned his craft from Nicolò Amati, was practically treated as a member of the family, and may well have owed his ability to establish himself in the premiere league of baroque Italian violin making to the fact that Amati's workshop had more business than it could manage.

Content overview:

- Andrea Guarneri – the pater familias

- Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri (I) – the faithful

- Pietro Giovanni Guarneri – Pietro da Mantova

- Pietro Guarneri “filius Joseph” – Pietro di Venezia

- Giuseppe Guarneri “del Gesù” – a true peer of Stradivari

It has not been clearly determined when Guarneri began training under Nicolò Amati; the late 1630s are plausible, but at any rate in 1641 he was documented as a member of the workshop and household. In 1645 Guarneri was a witness at Amati's wedding, which indicates a much closer bond than the one that would already have intertwined the life and work of a master and a journeyman in that era. It can be assumed that Amati regarded his talented student as a confidante who was a possible candidate for taking over his workshop later on – and Guarneri remained a person he continued to rely upon after his first son, Girolamo Amati, was born in 1649.

Upon marrying in 1653, however, Guarneri began to take steps towards establishing his own career and began to work as an independent master in the immediate vicinity of Amati. In a gesture of both respectful homage and of strategically wise alignment, he proudly designated himself "ex Allumnis Nicolai Amati“ on his first labels.

It is indeed true that Andrea Guarneri’s craft was predominantly defined by his teacher’s influence, even though the instruments of the student never quite reached the detail-obsessed precision and overall harmonious quality of his mentor’s work. Perhaps Guarneri was not familiar with the intricacies of putting the finishing details on a new instrument, since at Amati’s workshop the master himself usually performed those tasks.

It was not until many years later that Guarneri attempted a few innovations; the more closely positioned sound holes was one such endeavour that is not necessarily to be ranked among the more successful experiments in violin making history. By contrast, however, some of his few still-extant gambas are truly masterpieces that can hold their own against any other instrument. Another accomplishment was his smaller interpretation of the cello which corresponded to the growing soloist demands of the musical culture of his day. It ranks among the trail-blazing achievements of the original Guarneri workshop; as time passed, the influence of his sons’ work became evident at an increasing rate.

Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri (I) – the faithful

Andrea Guarneri's younger son Giuseppe Giovanni Battista spent his entire life following in his father's footsteps – as a student, journeyman and successor to the workshop, and later he remained there with the family he started in 1690. His close ties to his father and to the latter’s status as the second most influential luthier after Amati can also be seen in the label Giuseppe used from 1698 on, when he began to indicate that he was “filius Andreae.”

Despite the fact that Giuseppe Guarneri always remained true to the paths he pursued, his professional biography nevertheless indicates a few dark and enigmatic phases which hint at a troubled and turbulent life. The transition after Andrea's death was already fraught from a financial perspective, since Giuseppe had to pay out several heirs, including his older brother, Pietro, who had fallen out of favour. Shortly thereafter, Cremona became drawn into the chaos of the War of Spanish Succession which went on until 1707. And after stability returned following Austria’s victory, Giuseppe had to make his way under the same difficult circumstances his father had struggled with: he always came in second when the top luthiers of the era were compared. Andrea ranked after Amati, and Giuseppe ranked after Stradivari, who himself at the time was merely the most predominant luthier amongst the many competitors in Cremonese violin making.

It is thus no surprise that Giuseppe Guarneri’s oeuvre is very inconsistent, and in addition to creating true masterpieces in the art of violin making – which prompted no less a luminary than Charles Beare to name him one of the greatest violin makers in history – he also produced instruments made of remarkably simple materials and crafted with conspicuous shoddiness. From 1715 on, his sons offered him support, but his work abruptly ended in 1720, even though he went on to live for around another 20 years. Exactly why no more Giuseppe Guarneri instruments can be confirmed from this point onward remains one of the unresolved questions amongst musical scholars.

Pietro Giovanni Guarneri – Pietro da Mantova

Unlike his brother Giuseppe, Andrea Guarneri’s eldest son Pietro Guarneri did not spend his entire career under his father’s roof. Both brothers learned their trade at home, as it were, and initially stayed on after they had children of their own, but in 1679 Pietro decided to leave Cremona and move to Mantua – a step his father never forgave him for, but one which proved to be wise, since Pietro made a much better life for himself away from home.

In Mantua, a position at the court ensemble of Duke Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga secured Pietro’s livelihood after having been trained as both a violin maker and a violinist; ultimately he became known as “Pietro da Mantova” so as to distinguish himself from his nephew with the same name. Largely free of local competition, he was also able to establish himself as an excellent violin maker who made a name for himself in musical history. In contrast to Giuseppe, who had stayed in Cremona, it is clear that Pietro worked for clients who paid properly; consequently, he did not have to make any compromises in terms of the materials or labour he invested in his instruments. The resulting works included some exceptionally lovely violins and a cello, all of which are compelling in their elegance and a style which, while not revolutionary, is distinctive.

The fact that he created a fairly modest number of instruments – we now know of some 50 in total – was certainly due to his working at multiple tasks throughout his life. In addition to his music, he was also successful as a manufacturer of strings, and in 1699 the Duke granted him the privilege of a monopoly.

Despite the fact that his business clearly went well, Pietro Guarneri da Mantova remained without a successor; one can only speculate that he may not have had time to train one of his sons or another suitable apprentice. What is certain is that his art had an effect on other violin makers, including the Mantuese luthiers Balestrieri and Camilli – as well as his nephew Pietro Guarneri (“filius Joseph”) and his own brother Giuseppe, who followed more in Pietro’s footsteps than in his father Andrea’s in many ways.

Pietro Guarneri “filius Joseph” – Pietro di Venezia

The details of Giuseppe Guarneri’s biography cannot be documented after 1720, but it was during this enigmatic period that his son Pietro came into his own, the “Venetian Guarneri,” who was also known as Pietro di Venezia or “filius Joseph.” His first personal label is dated 1721, which is to say shortly after the time in which his father’s work appears to have ceased. It is thought that he then left Cremona and worked as an assistant to a Venetian master before becoming an independent master there. The first record confirming his presence in Venice is dated 1725, and there is evidence of at least a private connection to the Sellas (Seelos) family of lute makers.

As was the case for his uncle, Venetian Pietro’s decision to turn his back on Cremona was ultimately the correct one. Between 1730 and 1750 he created a formidable number of violins and a few celli which hold a special status in comparison with the other luthiers in his family. He did in fact uphold some of the Guarneri traditions, such as the structure of the table relative to the top and back, but in terms of his personal style, he merged the predominant influence of Stradivari with the Venetian tradition. In particular, the varnish (which plays no small part in how well an instrument sells) clearly reflected the preferences of the prevailing tastes of Venice at that time. And as was common in his new hometown, Pietro decorated his label with floral ornaments – but did not fail to include the attribution “figlio di Giuseppe” and a reference to his home town, “Cremonese.”

Giuseppe Guarneri “del Gesù” – a true peer of Stradivari

Whereas Pietro da Mantova and Pietro di Venezia Guarneri sought their fortunes (and found them) outside of Cremona, Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri ["del Gesù"] took a very different path than that of his uncle and brother after the apparent economic collapse of his father's workshop. Although little is known about the certain years in the life of the man who is considered the greatest luthier in history alongside Antonio Stradivari, it appears that he did little to pursue his art between 1723 and 1730; for the most part, the few surviving instruments from this period that might have been his work cannot be clearly attributed.

Upon returning to Cremona in 1731, he directly took up where he had left off as an apprentice and assistant in his father's workshop – and thus returned to an inspiring phase in which he had a great deal of creative liberty to experiment. This is a key reason as to why the late phase of the Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri workshop is now seen as the early phase in the oeuvre of Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù.

In the fifteen years that followed, del Gesù continued to experiment in his work. There were, however, three main identifying characteristics that served as a constant in all his pieces:

- His signature, which gave him his nickname and featured the Christogram IHS and an ornamented cross,

- His use of the unusual and linguistically archaic spelling “Cremonȩ” instead of “Cremonae”

- And of course the truly unique acoustic properties which elevated Guarneri’s violins into the ranks of instruments preferred by the world’s finest violinists such as Heifetz, Stern and Zukerman. This passion for Guarneri instruments began with Niccolò Paganini’s esteem for the legendary “Cannone.”

All of the other characteristics of the violin were subject to a constant state of flow with Guarneri, who was readily willing to break with all of the aesthetic and craftsman traditions – including those that his own family helped define – in his pursuit of a warmer and more powerful sound.

This attitude was already evident in his early work when he actively explored the innovations of his famous and highly successful neighbour Antonio Stradivari – quite unlike his father, who appears to have deliberately ignored the competition. Scholars attribute the significant acoustic improvement in of some of the Giuseppe Guarneri violins in the late 1710s to Stradivari’s influence, who had made his way into the Guarneri workshop via del Gesù. From 1730 onward, Guarneri turned his attention to the Brescia school and enhanced the table, silhouette and the position of the sound holes in keeping with the work of da Salò and Maggini.

Guarneri thus achieved his most notable accomplishments around 1735, and his historic legacy is due in no small part to his brilliant craftsmanship and success in blending the finest characteristics of the Cremonese and Brescian traditions, the two most influential and highly refined Italian violin-making schools.

The remaining nine years until his early death were marked by an increasing disregard of all of the aspects of the violin that were incidental or irrelevant to its sound. As a result, Guarneri emphasised acoustic properties more and more as he selected his woods, not allowing himself to be charmed by even the loveliest of grains. The execution of his work became hastier and more marked by evident disinterest; the colour of the varnish became more a matter of coincidence; the sound holes were not symmetrically carved and seemed to be positioned more by the master’s intuition of the top’s vibration properties instead of by aesthetic concerns.

Unlike Antonio Stradivari, Guarneri del Gesù did not implement the principle of trial and error during only a single phase of his oeuvre: he did so until the very last day of his working life. Perhaps it is this brilliant spirit of openness which has allowed Guarneri violins to enjoy some of the popularity they continue to experience amongst outstanding artists – not to mention the excellent sound, which continues to set standards some 300 years later.

Related information:

Antonio Stradivari - a story of sound and echoes

On the life of the Tyrolean violin maker Jakob Stainer

Jérôme Thibouville-Lamy (J.T.L.)

Useful links:

Library - text about the history of stringed instruments

Online catalogue | Premium violins, violas, cellos and bows (audio sound samples)