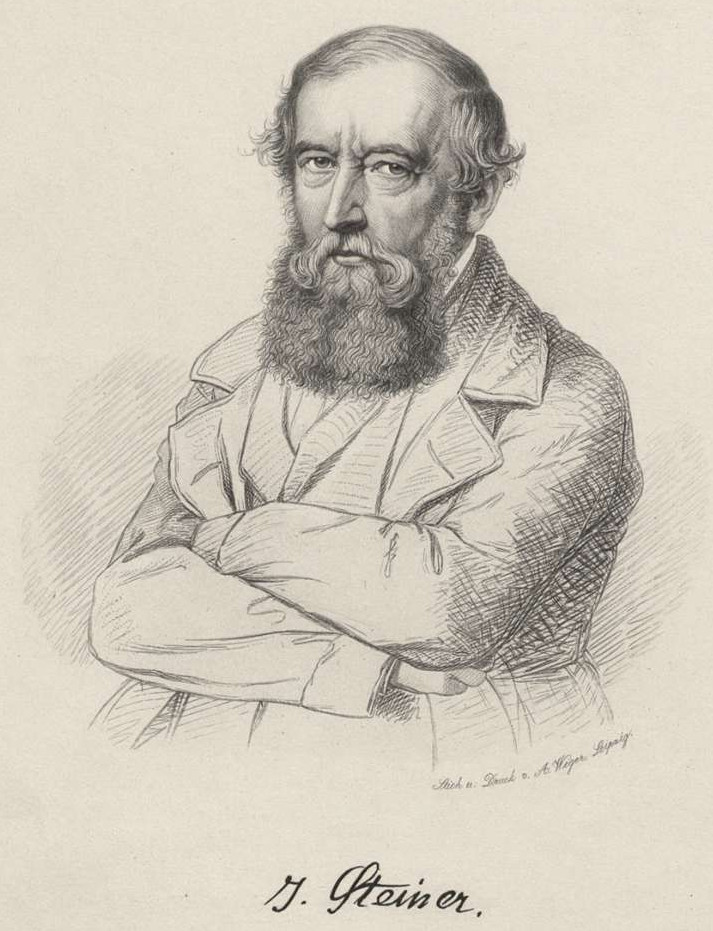

On the history of Jakob Stainer (Jacobus Stainer), a violin maker in an era of uncertainty

The life story of the tyrolean violin maker Jakob Stainer (1618-1683), also called Jacob Stainer / Jacobus Stainer, who lived in Absam near Innsbruck and Mittenwald, is an enigmatic blend of coarse anecdotes, unparalleled artisanal achievements, and a spirit that was surprisingly contemporary. The resulting biography paints an unconventional portrait of the paradoxical historical period, the epoch at the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War in which the most important European luthier outside of Italy was born. In its peaks and troughs, Stainer’s biography reflects the tensions of its day, an era of uncertainty which yielded a musical luminary who was restless and repeatedly failed whilst still setting standards.

The story of Jakob Stainer: Overview

- Jakob Stainer's early life

- The apprentice years: Was Jakob Stainer a student of Amati?

- A journeyman's wandering: Jakob Stainer as a young luthier

- A story of financial drama

- Stainer establishes himself in Absam

- Rough edges: Jakob Stainer as a product of his time

- The heresy trial again Jakob Stainer

- Economic turbulence

- Jakob Stainer's illness and death

- Notes on Jakob Stainer's oeuvre

Jakob Stainer's early life

Jakob Stainer’s life began in some of the most simple and impoverished circumstances imaginable. He was born as the son of a miner sometime around 1618 – although scholars discuss varying dates between 1617 and 1621. Nevertheless he was able to go to school and received basic musical training as a member of the boys’ choir in Hall or at the court of Innsbruck. Statements in later letters would imply that he at least learned the basics of playing the violin, a qualification he later described as being “quite necessary and useful” for violin makers.

The apprentice years: Was Jakob Stainer a student of Amati?

Historic research has not been able to determine exactly how Jakob Stainer found his way to violin making, and the question as to his teacher remains a mystery that has given rise to a great deal of speculation. Did he complete the first years of his training with a carpenter in his home region of Tirol, as the rules of his guild dictated? And did he then go to Cremona or perhaps even work in the famous Amati workshop, as one enigmatic violin label would imply? We do not know. There is a great deal of evidence that Jakob Stainer knew about the innovations of Italian violin making – and knew them well – but as a young craftsman in training, he focused intensely on southern German traditions. His greatest legacy on musical history was the way in which he perfected this tradition and turned it into the standard of an era in violin-making history. It is thus conceivable that he may have been trained in Italy but with a German luthier who lived there, perhaps in Venice where he apparently had ties; there is, however, nothing to corroborate this hypothesis.

A journeyman's wandering: Jakob Stainer as a young luthier

In the late 1630s Jakob Stainer had established himself within his field and was leading the life of a wandering craftsman who sold his instruments directly to those who commissioned them, to other interested parties, or at markets; otherwise he earned his living by making repairs wherever they were needed. In his home of Tirol, several such opportunities presented themselves thanks to the dynamic trade that took place along the road between Verona and Augsburg, a route that still exists today as the Autobahn A12/E60 and connected the villages along the Inn valley like a string of beads. His earliest signed violins date back to the year 1638; a sale to the Salzburg court was documented from the year 1644, and commissions from Munich and the court of Innsbruck followed shortly thereafter. These transactions confirm the growing successes of the young luthier who was able to increase the price of his violins from around four guilders to around 20 in this period, and he was also able to start a family during in 1645 in the midst of these gradually improving circumstances: his first daughter was born just before he married Margareta Holzhammer, the daughter of a mining foreman from Hall. In keeping with the sad statistics of the day, only three of Jakob and Margareta Stainer’s nine children survived their parents.

A story of financial drama

One of the defining characteristics of Stainer's biography was the debt that marred his career from an early phase onward. These business challenges opened certain doors to him ‑‑ the son of a miner ‑‑ but they also followed him, not only throughout his life but beyond his death as well. The period in which Stainer created the majority of his oeuvre as a luthier and became one of the most influential figures in European violin-making history can also be told as a story of financial drama: loans taken and granted, interest payments, arrears and massive liquidity crises. To a certain extent, Stainer's biography is thus typical for the transition to early capitalism, which was one of the major developments of its era.

Even the earliest documents of his business arrangements serve a stellar example of this situation. In 1646 Jakob Stainer took on a debt that had belonged to his father-in-law, who had become financially overwhelmed by his obligations as a mine foreman and owed Archduke Ferdinand Karl a considerable sum. Stainer offered to pay the debt by providing the Archduke instruments and gradually let his father-in-law repay him. This was a remarkable and clever manoeuvre which both allowed the young luthier to sell his violins whilst also creating a point of access to the Archduke’s court. Stainer ultimately received a payment of 50 guilders for the initial delivery of 30 guilders’ worth of instruments and strings – and immediately put these short-term liquid assets towards a trip to Venice with the express goal of purchasing raw materials.

This business trip lasted around a year and a half, and when Stainer returned, the family debt was transferred to court musician Christoph Hegele and then cancelled shortly thereafter. This was an odd end to this transaction and triggers speculation: perhaps the court had lost patience after Stainer's long absence? Had the entrepreneurially inclined master discovered new and better options? These are some of the many unresolved questions about Jakob Stainer’s biography.

Further journeys led Stainer, ever the wanderer, to Munich, Venice, Bozen and Brixen from 1650-55. The fact that he became godfather for the first of many times in 1652 and personally served as a guarantor to a bond in 1653 both indicated that his financial situation and, by extension, his bourgeois status had stabilised. In 1655 he sold an elaborately ornamented violin in Munich for 30 guilders – the same sum he had owed the Archduke only a few years earlier and for which he had parted with several instruments to settle his debt.

Stainer establishes himself in Absam

His growing successes and an inheritance allowed him to settle in Absam in 1656 and open a workshop. He acquired the house where he was to work and spend the rest of his life; he did so by swapping houses within the family and paying his relative the difference of a hefty 150 guilders, for which he went into debt.

In 1658 Stainer was appointed an Archducal servant and purveyor to the court by Count Ferdinand Karl of Tirol as a belated reward for his many years of service at the court of Innsbruck. This title was a key factor in his success; as an immediate result, he received commissions from the Spanish royal court, and the radius of his influence steadily expanded well beyond the borders of German-language countries and even to Italy. Composer and virtuoso Antonio Veracini, for example, owned 10 Stainer violins, which comprised half of his collection.

Rough edges: Jakob Stainer as a product of his time

Jakob Stainer lived in the conflict-rich period of the 17th century, an era of political and societal unrest and upheaval, of transition that affected every aspect of people’s lives. Stainer’s life played out in Habsburgian Tirol, one of the key regions of the Counterreformation – a place which nevertheless was affected by revolutionary Protestant teachings that made their way even to the smallest villages, sometimes openly and sometimes in a clandestine fashion. The financial turmoil generated by the Thirty Years’ War and the growing economic pressures of the nobility had an impact on every class of the restructuring society; consequently, it comes as no surprise that a luthier such as Jakob Stainer also experienced his share of the tensions of his era. This was all the more true since the documents which have survived all depict him as a man who was unusually well educated for his social status and as an intelligent but difficult character.

Amongst the more minor conflicts in the "Stainer files“ was a physical altercation with Absam peasants in 1659 which ended in mutual claims filed for damages. In 1661 Stainer was forced to appear in court for a dunning trial involving an invoice he had contested, and he was sentenced to pay 50 guilders.

The heresy trial again Jakob Stainer

In addition to these minor legal skirmishes, there were formal legal charges of heresy against Jakob Stainer and his friend Jacob Meringer, who had been Stainer’s employer for over two years from 1668 onward. The two ended up in prison, and the incident helped solidify the historic image of Stainer as a rebellious personality who was literal-minded to the point of obstinacy. The secular courts attempted to remain uninvolved in the dispute as much as possible, but the formal accusation was that Jacob Meringer owned banned books that that criticised the church. Meringer attempted to defend himself by saying that he had received the books from Stainer. The real issue was probably a denunciation, since Stainer’s relationships to those around him was not always unclouded, and the eloquence he exhibited in the course of the trial may well have further stirred up additional conflicts in the small community of Absam. The fact that this kind of conflict amongst neighbours must have been at the heart of the matter can be seen in Stainer’s and Meringer’s repeated requests that the authorities should simply name the people who had testified against them. The more this request was ignored, the more vehemently they boycotted the proceedings; Stainer repeatedly asserted that he was unable to appear in court due to his heavy workload and the prestigious commissions he had to fulfil. The escalation landed both of the accused parties in jail, where they were able to negotiate their sentences down to a moderate ritual of penance. This, however, did not stop them from immediately attempting to sue one another (albeit unsuccessfully) for loss of wages and expenses related to their legal fees.

It ranks amongst the paradoxes of this period that although Stainer was on trial for heresy and was even excommunicated for a time, his business was allowed to continue unimpeded. Even whilst under house arrest, he successfully received a major commission from the Bishop of Olmütz, and during the trial he delivered instruments to Vienna, complete with imperial customs privileges. The Archduke's letter of trade which had granted Stainer his position as a purveyor to the court expired in 1662, but it too was renewed in 1669 under imperial privilege – which casts a highly distinctive light on the relationship between secular and clerical power in the staunchly Catholic empire of the Habsburgs during the Counterreformation.

Economic turbulence

In this period of both turbulence and success, Jakob Stainer was forced to deal with more and more economic problems, some of which could be attributed to his own financial mismanagement and some of which were due to the unwillingness of his clients to pay, not to mention the manner in which financially pinched authorities dealt with their debts. The family was saved in 1667 by re-structuring its financial liability when Stainer was unable to repay the loan he had taken out 10 years earlier to buy his house. He had to write off the deceased Archduke’s old debt of 450 guilders in 1677 when the royal court refused to assume its obligations as the legal successor to the through when the Habsburg line died out with Ferdinand Karl.

Despite the fact that Stainer’s instruments were still in high demand, he often had to make painful concessions. One such example was the 1678 sale of a gamba to Ferdinand Stickler, the deacon of the Meran parish church. Stickler wanted to pay for the instrument in wine, but Stainer offered him a massive discount for paying in cash. He charged 16 thalers for the gamba although at other times in his life he could have sold it for twice that amount, and at no additional cost he volunteered to include a lion’s head instead of a scroll and to take the instrument back if Stickler was not satisfied.

Jakob Stainer's illness and death

It can neither be proven nor ruled out that these problems played a part in the ongoing decline of Jakob Stainer’s health, a development which began around 1675 and had an increasing impact on his business affairs from 1680 onward. The sources available to historians make it impossible to provide a medical diagnosis, yet Stainer’s business correspondence from this period creates the strong impression of some sort of a psychological disorder, if not even manic depression, even though – amazingly – his artisanal skills remained unaffected. It is in this very phase that his most beautiful instruments were crafted, and in 1679 he received a major commission from the court in Munich to produce several instruments; they paid him a deposit of 150 guilders.

These pleasant developments were not enough to reverse his situation, however, and in 1682, after he once again failed to make an interest payment, Stainer was placed under legal conservatorship. His son-in-law, Blasius Keil, had been married to Stainer’s daughter Maria, who died in 1678 or 1679, and Keil intervened and accepted the proposal of the official conservator that he purchase Stainer’s house while giving Jakob and Margareta the right to remain there until their deaths. Before this plan could be implemented, Jakob Stainer died in the fall of 1683; the exact date of his death is not known. His wife Margareta followed in 1689.

Epilogue

In 1694 Blasius Keil was summoned to court because he had failed to pay the primary interest for the home he had inherited. The debts which had become a life-long issue for Jakob Stainer haunted his legacy as well.

Notes on Jakob Stainer's oeuvre

Jakob Stainer’s last violin was created in 1682 shortly before his death, and the instrument can now be found in the national museum Ferdinandeum in Tyrol, Austria. Despite the fraught conditions under which he crafted his later pieces, his work reflected a markedly high standard until the very end. Given the major consistency of his widely-imitated personal style, it is difficult to differentiate between the various phases of Jakob Stainer's oeuvre, which is not the case with many other great luthiers. In addition to the characteristic shape of the sound holes, one defining feature of Stainer’s model is the high table (i.e. the high arch of the top). Without elaborating here upon the details of how he shaped his tops and backs, it can still be stated that the height of the table may have created a striking distinction in comparison to the Stradivari model which later became predominant; nevertheless, the truly inimitable characteristic of Stainer violins is its remarkable plateau-like design of the top, especially compared to other high-tabled violin models in German-speaking countries. To a lesser extent, the remarkable quality of Jakob Stainer's violins is also due to individual details of his model which, regarded individually, explain the mystery of the voce argentina (“silver voice”) that was so widely sought after well into the 18th century. Comparable to the oeuvre of Antonio Stradivari, the decisive factors were ultimately Stainer’s talent, significant experience and the uncompromising care with which he crafted his instruments – starting with the tone woods he chose which he personally selected during the course of days of hiking through the valleys of his home. He stated that he found the best trees by their scent, sound and colour.

Contrary to assumptions made by earlier scholars, Stainer did not pass his knowledge along to any students; instead, throughout his career he mostly worked alone and achieved his wide-ranging influence only through the quality of his instruments and the excellent reputation which spread internationally even during his own lifetime. For example, the English violin-making tradition as a whole followed exclusively in his footsteps for many years, and he served as a major role model even in “cradles” of violin making such as France and Italy – where countless masters and workshops produced legions of counterfeit Stainer labels for the higher- and lower-quality violins they produced, a legacy that still occupies scholars of instrument history to this day.

Originally published by Corilon violins.