Matthias Klotz, the Klotz violin and its forefathers: a family tradition poised between mastery and brand recognition

Matthias Klotz provides the finishing touch: with the experienced eye of a master, the Mittenwald violin maker picks up the blade to complete a new violin. His work is astoundingly delicate, given his large physique and powerful hands. The Matthias Klotz statue in Mittenwald has had him frozen in this position since the autumn of 1890, and the famed iron caster Ferdinand II Freiherr von Miller rendered him with almost startling accuracy in detail – and is said to have considered this piece his best work. “We don't want a symbol — we want to see the man himself,” as the members of the Mittenwald violin-making association told von Miller. The memorial they commissed is the perfect portrait of a craftsman, an artist of whom there are no photographs. The statue draws the observer into a dialogue with multiple parties: with the internationally active merchant Neuner and Baader, who recognized the value of the “Klotz brand” for Mittenwald and arranged for this monument to be built; with the artisan craftsmen in a small Bavarian town where violin making became a gift from heaven and which is pleased it can mention its great son in the same breath with Amati, Stainer and Stradivari; and last but not least, with the countless apprentices and journeymen who since Matthias Klotz' era have spent their in days in small workshops and large manufacturing halls, stooped over their benches and in constant motion, much as Matthias Klotz (Matthias Kloz) himself appears to be on the statue in front of the Mittenwald St. Peter and Paul church.

Content overview:

- How did Matthias Klotz become a violin maker?

- Establishing Matthias Klotz’ Mittenwald workshop and its first successes

- Sebastian Klotz – the classic of Mittenwald violin making

- The characteristics and historical value of the Klotz violin

- Georg II and Aegidius Klotz

- The Klotz violin in the context of German violin making traditions

How did Matthias Klotz become a violin maker?

A look at the early history of violin making in Mittenwald does indeed resolve many questions, but it leaves just as many unanswered. Its key figure was Matthias Klotz, since it was this tailor's son who raised the art of violin making in his hometown to the art which brought about its growth in the upper Isar valley. However, practically nothing is known about Matthias Klotz's background; there is no information about how he became a luthier or where he underwent his early training.

And an even greater enigma involves the instruments he produced in the first three decades of his working life, since his oldest surviving instruments date back to the year 1712 – when he was 59! This remarkably large gap in information has never been satisfactorily filled. One hypothesis states that Klotz built only a few violins, if any at all, in his earlier years. If this theory were true, however, there would be no explanation for the masterful quality of his later instruments. It is equally implausible that every single one of his earlier pieces disappeared or went unrecognized, given his relevance in the history of musical instruments.

It can be safely assumed that Matthias Klotz relates to the influential school of lute makers from Füssen; beyond that, we also know that he also pursued some of his training in Italy, as a journeyman's certificate from Pietro Railich in Padua confirms. Whilst it is often stated that he studied under Nicolo Amati and worked for Jacobus Stainer, these claims belong more to the undefined contours of his biography which blur into legend. It is all but impossible to make definitive statements about his work, given the limited information available, and in the meantime it is also clear that he is not seen as the first luthier in Mittenwald's history. Nevertheless, his major success and his significance in the annals of Mittenwald violin making cannot be disputed. The atelier he established in the 1680s seem to have brought him excellent business opportunities from the very outset. The timber of the Karwendel mountains ensured a rich supply of premium tone woods, and Mittenwald's location along an important trans-Alpine trade route offered him advantages as a merchant. Furthermore, Klotz had almost no local competition.

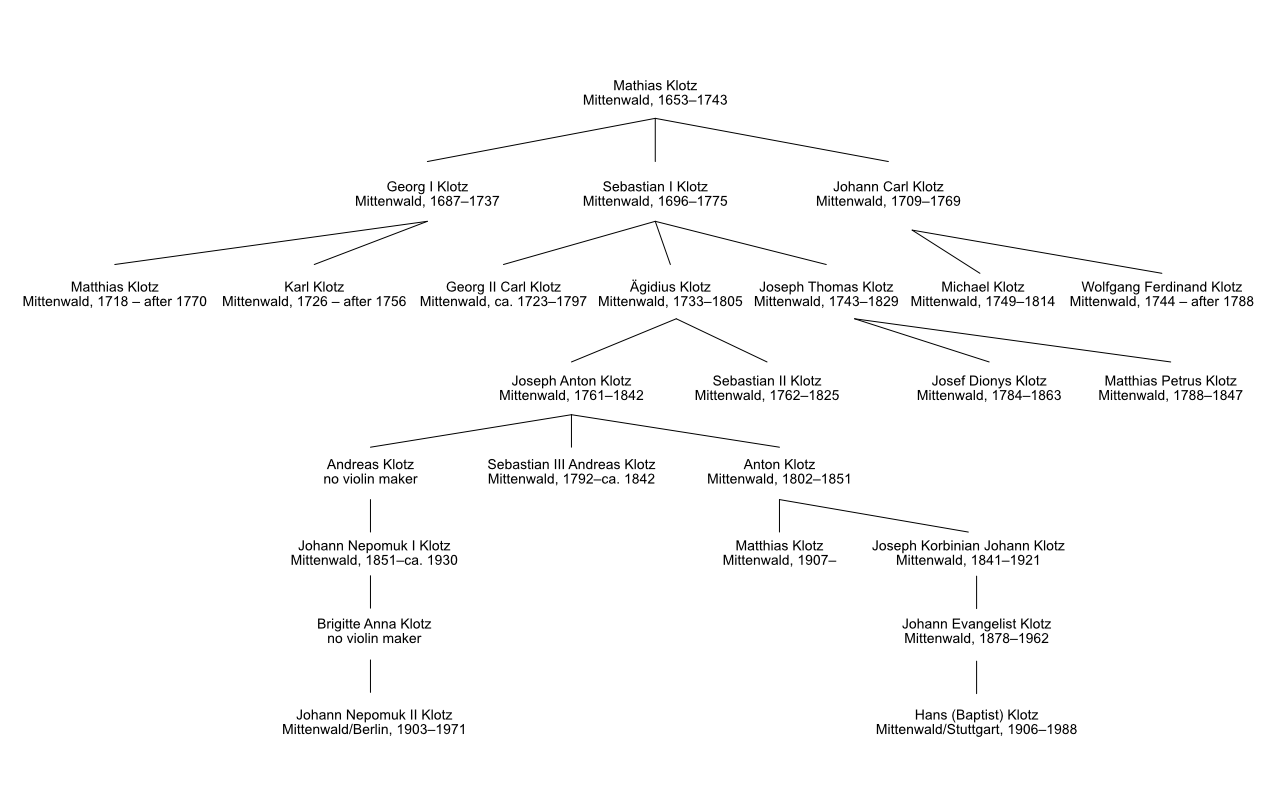

Klotz violin makers family tree

Establishing Matthias Klotz’ Mittenwald workshop and its first successes

His flourishing atelier was able to employ numerous apprentices and journeymen who themselves went on to found important families of luthiers. Alongside the masters who emerged from the Klotz studio such as Andreas Jais and Martin Tiefenbrunner, the many members of the Klotz dynasty itself contributed to the history of their pater familias' influence. As was the case in many comparable large families of craftsmen, the interplay of mutual influences and interdependence is as interesting a field of research as it is broad. In a long sequence of over 25 luthiers spanning eight generations, the Klotz family maintained a critical role in the violin making of their hometown until the late 18th century. And to the extent that the works of individual family members have survived, they confirm a tradition of talented and well-trained craftsmen who understood how to link individuality and creativity with their faithfulness towards family customs. Even unique models such as the outstanding ones by Matthias „Dax“ Hornsteiner, who worked in the second half of the 18th century, do not in any way detract from the impact of the Klotz violin; instead, both the traditional and the innovative models appear concurrently as evidence of a regional form of craftsmanship which continued to evolve and become more nuanced.

Sebastian Klotz – the classic of Mittenwald violin making

In the first generation after Matthias Klotz, the most important proponent of his art was indubitably his son Sebastian Klotz. If the surviving instruments are any indication, the son exceeded his father-cum-teacher's talent and creative abilities, and Sebastian too had a lasting influence on violin making in his home town. Sebastian Klotz's model is regarded as “the” Klotz violin in the stricter sense of the word, and Sebastian Klotz' independent artistic contribution to violin-making history may in fact be greater than that of Matthias. Nevertheless, a memorial was never built to Sebastian Klotz, and whereas Matthias Klotz advanced to become an icon of Mittenwald violin making in the 19th century, the only thing speaking for his son is his instruments – along with the works that followed by his sons, students and numerous imitators.

The characteristics and historical value of the Klotz violin

In the history of instruments, the Klotz violin design blazes its own trail amidst the prevailing role models which shaped the art of the day: the Italian tradition of Nicolo Amati on one end of the spectrum, and Jakob Stainer's German style on the other. It should not go unmentioned, however, that Sebastian Klotz's oeuvre is marked by a wide range of variety. He seems to have given himself and his employees a great deal of artistic liberty, at least by the time he had achieved the zenith of his craftsman development and established himself successfully. This leeway was not only evident in purely aesthetic details, such as modifications to the varnish or the shape of the scroll. It can also be witnessed in key questions of the luthier's work, such as the length of the body, the belly stop and the height of the ribs. Despite these stylistic variations, it is still possible to pinpoint characteristic features of the Klotz model: a moderately high table, typical lines in the fluting of the arches and edges, a curved peg box and a confidently-shaped scroll with a high throat radiating baroque lavishness. The trained eye will also see important and distinctive details on the interior of genuine Klotz violins, especially in how the corner blocks and lining were crafted. One-piece upper and lower ribs and a thin coat of intense brown varnish are further identifying characteristics of instruments from Sebastian Klotz's atelier.

Georg II and Aegidius Klotz

The most important common, if not defining, characteristic of the work produced by the third generation of the Klotzes and their apprentices also reflect elements of variation and the further evolution of the family heritage. Georg Klotz, Sebastian Klotz's oldest son, initially based his work on his father's model but gradually found his way to a broad style of his own. This was apparent not only in the unusually large instruments he crafted which set him apart from many luthiers of his day; Georg Carl also pursued his own approach in designing the arch, the fluting and the sound holes. His brother Aegidius Klotz took even more independent steps; his shape has short upper bouts with an unmistakable, slightly compact character emphasised by the comparatively broad purfling. The variations in the belly stops are much greater in Aegidius Klotz' instruments than in those of his father Sebastian and his atelier, where Aegidius Klotz was very probably trained. Aegidius Klotz also created his own distinctive design for the scroll which can be easily recognized by its very short throat.

The Klotz violin in the context of German violin making traditions

It is because of these individual accents that the history of the Klotz violin confirms many native traditions which defined the historic interval between Stradivari and the widespread embraceing of classic Cremonese violin-making principles. Each of these traditions bore its own fruit and had different levels of normative power, but they also brought about viable new standards. In this sense, Sebastian Klotz can be compared to someone such as the Klingenthal luthier Caspar Hopf, who was a talented craftsman of similarly innovative strength and lingering influence, at least on a regional level. Another regional tradition to receive renewed appreciation in recent days is that of the rustic-natured baroque instruments crafted by the Alemanni school in Switzerland and the southern Black Forest. This new interest is not only a topic favoured by museums and academia; instead, the artistic approach of the historic-music movement has been responsible for these instruments earning respect as “musical eyewitnesses” of their time, both in theory and in practice.

This relatively new and nuanced perspective of the history of stringed-instrument making loosens the scholarly corset strings, as it were, allowing the Klotz violin to breathe and gain some distance from its monumental historicization. It also shows once again that the gradual decline of the schools other than Stradivari was not due to concrete obstacles. Instead, the end of the Klotz era (and of similar eras in other places) had a great deal to do with the publishing business and the industrialisation of violin making, which in turn brought about greater conformity of craftsman standards and revolutionised the stringed-instrument market. These developments fundamentally changed the function of traditional craftsmanship and its distinguished masters. As a result, they did not disappear outright, but they began to play a new and less influential part. Or, as was the case with Matthias Klotz, they became mythical sources of inspiration to their followers, who had long since begun producing for a global market.

Dr. Annette Roeben, founder of Corilon violins, donated a rare violin by Matthias first son to the Mittenwald museum: a violin by Georg I. Kloz, 1722

Related information:

The Mittenwald violin making competition and other international contests

Contemporary violin makers - the modern artisans

Markneukirchen: violin making in “German Cremona”

Hopf: a dynasty of Vogtland violin makers

W. E. Hill & Sons – on the Mt. Parnassus of the art of violin making

On the history of industrial factories in Mirecourt

How to select a violin: provenance, value and violin appraisal